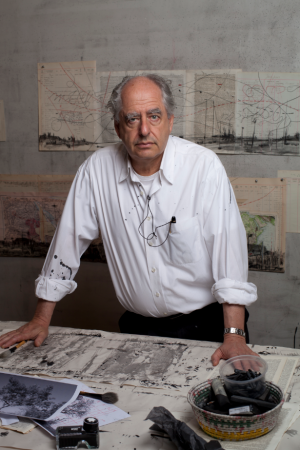

威廉·柯ntridge

Artist Bio

威廉·柯ntridge uses drawings to create films. In his works, unlike in traditional animation that employs multiple drawings to denote change and movement, Kentridge erases and alters a single, stable drawing while recording the changes with stop-motion camera work. He modifies the drawing slightly, goes to the camera, and begins what he calls “the rather dumb physical activity of stalking the drawing, or walking backwards and forwards between the camera and drawing; raising, shifting, adapting the image.” The result is a hybrid of drawing and film that has been highly praised for both its innovative manipulation of media and its ability to look at troubling social issues in a way that is neither sentimental nor aggrandized.

South Africa, where Kentridge was born and continues to work, is the focal point of his studio practice. Kentridge addresses apartheid and other social wounds without tackling the issues head-on, making them susceptible either to redemption that comes too easily or to a rendering of their history that is too spectacular. He enters into historical discussions through the lives of three fictional characters: Soho Eckstein, Mrs. Eckstein, and Felix Teitelbaum. Their individual lives are set against the wide, political landscape of South Africa as well as the deeper forces of life like renewal and destruction. The various vectors of thoughts, feelings, and inner turmoil of the characters, represented sometimes by animals or lines or other markings, spill across Kentridge’s images and frames. The personal and public become critically mixed, neither free of guilt nor completely capable of redemption.

InStereoscope, 1999 Soho Eckstein is portrayed as interconnected with both images of the social injustices and upheaval of South Africa and his own sort of primal, fractured existence. The stereoscope, a device used to unite split images into the illusion of a coherent visual field, represents exactly what Kentridge does not allow in the film. He instead uses his method of erasure to move between disparate images and situations, not a presentation of a unified field but a shifting scene of energetic connections and splits. The result is a work that can face the humanity of the individual without expunging guilt and address larger issues in society without trite, easy solutions.